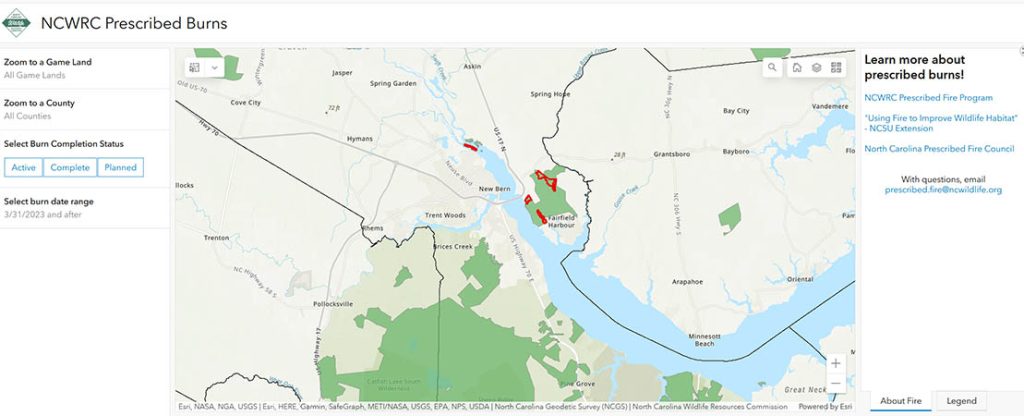

N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission introduced a new webpage with an interactive fire map that allows viewers to see “near real time” information related to their prescribed program on game lands. See the status of active, complete or planned prescribed burns throughout the state by clicking here.

Recently, Governor Cooper announced February as Prescribed Fire Awareness Month in the following news release:

Prescribed Fire: Smoke In the Air

For centuries, people have used fire as a tool to manage natural resources. Before European colonization, Native Americans used low-intensity, controlled fires to clear brush and make room for wildlife – a practice that we still utilize in modern-day forest management for the betterment of wildlife and habitat.

“Prescribed fires” or “controlled burns” are intentionally ignited and professionally controlled low-intensity fires that are used for a number of habitat improvement purposes. Teams of professionally trained foresters manage these fires and keep them from getting out of hand, ensuring that the fires do their work only on the intended forest area and nothing more.

Critical to forest health, prescribed burns achieve numerous benefits for wildlife and habitat. They reduce the buildup of brush and vegetation, decreasing the chance of uncontrolled wildfires that could cause significant damage to natural areas, wildlife, and surrounding communities.

Over the course of their evolutionary history, many plants and animals have become used to and even reliant on fire to survive and thrive. Prescribed fires help to reduce competition, release seeds, and add nutrients to the soil – which benefits many native plant species, a critical food and habitat source for wildlife. Additionally, the use of prescribed fire helps to cull overpopulated forest areas, allowing more room and resources to the plants that need it most.

Though prescribed burning benefits entire ecosystems and a wide range of wildlife species, there are individuals who tangibly benefit from the results of prescribed burning. The red-cockaded woodpecker is one such species.

Red-cockaded woodpecker

Once a common species throughout long-leaf pine ecosystems, the red-cockaded woodpecker is now critically endangered due to the decimation of critical habitat following increased farming practices throughout the state, urbanization, and the failure to utilize prescribed burning as a means to provide essential long-leaf pine habitat for the species. As a result, according to NCWRC, the reduction of suitable habitat has caused the number of red-cockaded woodpeckers to decline by approximately 99% since the time of European settlement. Once considered a common species, the red-cockaded woodpecker now tragically boasts a mere 14,000 estimated remaining birds across eleven states.

Prescribed Fire: A Golden Ticket for Wildlife and Habitat

Through the utilization of prescribed burning, endangered wildlife species such as the red-cockaded woodpecker may stand a chance of rebounding – and other species and habitats can be kept out of harm’s way.

NCWF is working with federal and state agencies to ensure that 1 million acres of National Forests in the North Carolina mountains – particularly the Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests – will be managed in a responsible manner, one that maintains healthy habitats and restores those that have been rendered inhospitable for many species. According to CEO Tim Gestwicki, prescribed burning is front and center in these plans as new-growth ecosystems and young-growth forests produced by prescribed burning are needed in order to support a range of species, from elk populations to golden-winged warblers.

Long-leaf pine forest with a clean understory, a result of prescribed burning

Often, people are afraid of the effect that prescribed burning has on wildlife, imagining raging fires advancing toward helpless and confused fleeing wildlife. However, it is important to remember that controlled burning utilizes as little fire as possible to accomplish the task, allowing animals plenty of time to get out of the way of the flames – either through running, flying, climbing, or burrowing away from the flames. This is largely due to the reality that fire is a natural occurrence to which animals have adapted over the course of history. Once the fire has gone out, wildlife in the area may be slightly disoriented, but quickly adjust to their new surroundings and welcome the new growth of native plants rising from the ashes.

Without the use of prescribed fires, plants in the understory are allowed to run rampant and choke out other plant life critical to these ecosystems. Not only does this knock the ecosystem off balance, but makes some habitats inhospitable to wildlife native to these ranges. While alternative management methods such as herbicide and machinery use can be effective, they are often more expensive and can cause more collateral damage to plants and wildlife than what is caused by controlled fire.

Late winter and spring, typically between January and March, is referred to as the prescribed burn season, when most trees are less active metabolically. Repeated burns, conducted during the spring growing season, will eventually kill suffocating hardwood sprouts and allow a diversity of native grasses and wildflowers to develop. These native plants offer a source of food and habitat far more desirable to species that benefit from long-leaf pine ecosystems.

Ultimately, the use of prescribed burning ticks many boxes for the good of wildlife and habitat… but also for the people living within the state of North Carolina. With increasing human populations throughout the state and the accompanying infrastructure needs required to support expanding communities, prescribed burning is all the more important in science-based forest management. For the safety of all species living throughout the state, and for the flourishing of biotic communities, prescribed burning for the purpose of creating fire-adapted plant communities is a no-brainer for wildlife and habitat.

Information provided by NCWRC and NC Governor’s Office

By Wendy Card, co-editor